For cult fans of Chuck Palahniuk’s self-destructive, freak protagonists, Diary provides the satisfactory quencher for bloodlust. Diary opens with a harrowing premise centered on the attempted-suicide of a contractor, Peter Wilmot, and the “disappearing” rooms in Waytansea (“Wait and See”) Island. The reader is introduced to three women--the elderly mother Grace, the haggardly wife Misty, and Tabitha, the daughter--torn by the imminent loss of their Peter, who lies comatose in the hospital, and the Wilmot family home. Palahniuk wastes no effort indulging sadistic fascinations. Coma be damned at Peter's beck and call, Misty Kleinman pushes broach pins through his skin while she reignites her passion for painting.

Misty, a hotel waitress and the hapless heir to the Wilmot family curse, records the destitute humiliations and mysterious headaches she endures in her coma diary with Peter. With expert graphologist, Angel Delaporte, she investigates Peter’s scrawled writings in a hidden room in the Wilmot home. In much the same way Matheson’s What Dreams May Come privileges a journal as the medium for communication between the dead and the living, Misty‘s diary and Peter’s wall scribbles guide the blighted lovers through Misty’s rise and fall from artistic apogee with none of the sweetness of Almodovar’s Talk to Her but all of the creepy revelations. The victimized women, yes including Grace and Tabitha, to whom we give condolences eventually betray graver motives that are not made clear until later.

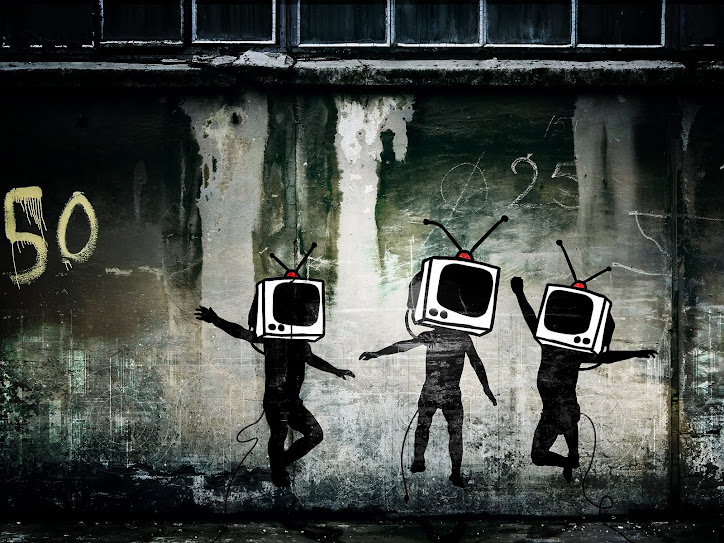

Palahniuk’s colloquial prose and steady pace sustains the reader through convoluted art lessons punctuated by nihilistic caveats of “what they didn’t teach you in art school.” Similarly with Haruki Murakami novels, Palaniuk makes the reader work, filtering through the metaphysical and psychological miasma. Then, the tragic hero's journey to discover, in every visceral sense of the word, cathartic release ends up severing her like a textbook Sybil. This trope, a shock ending that reveals an ego-centric verisimilitude that exists alongside a more tragic, repressed reality, was employed in a related manner with a narrator and his alter-ego in Fight Club. Yet, the realization of the doppelganger delivers a greater punch in the latter since in Fight Club the narrator and Tyler Durden co-existed for most of the story duration and is the penultimate big bang. By the time the reader is led through the gallery of horrific yet provocative caricatures and scenes, of which the narrator alternates beween the omniscient and Misty, the final chapters jerk like a rickety roller coaster with the gratuitous vomit and piss.

Just when the art schooling, for which Palahniuk clearly did his homework, sounds a bit like sententious prattle (about the sanctification of art and the necessary sacrifices), bodies fall and phantom figures appear. Misty trips and breaks her leg, Angel (who surprise, surprise was Peter's gay lover) is murdered, and her daughter supposedly drowns. Detective Stilton and Harrow Wilmot (Peter’s father) weave in and out of Misty’s fog of consciousness and Tabbi, quite literary and figuratively, leaves a blazing trail for Misty. The long anticipated denouement comes after the reader is made to trail many a squalid litter of Macguffins.

Misty’s paranoia explodes into a community-orchestrated conspiracy. Misty’s torments as a result of her artistic genius becomes the sacrificial offer fated to save Waytansea Island. The profound pause Palaniuk allows for paranormal eeriness behind the perfect angles and curves of Misty’s paintings and the exact depiction of the never-before-seen Hershel Burke chair, perhaps a nod to Vincent Van Gogh’s Chair, is effective. The schizophrenic jumble of epiphanies and frenetic pace that mirrors Misty’s mental disintegration is a questionable literary device in this case. The morbid Sondheim-worthy refrain, “kill every one of God’s children to save our own” (which seems to be the moral behind Misty’s realization that Tabbi may be her dearest treasure) is drowned by the many voices in both her and Palahniuk’s head.

Sunday, May 30, 2010

The Tree House of an Irian Jaya

Slow, the dandy Korowai sips

his coffee. A fetid scent

of sago palm fronds billows

upwards to rattan-latticed frieze,

a wispy lick of the facade

of animist caricatures. The cannibal muses

as the purr of Kopi Luwak settles,

steeped in carrion-coated deals and

polyglot grunts and grumbles

from the electric donut.

Human flesh differs naught from pig

when raised to a green empyrean

nestled on thirsty cement roots

crust with salted grime.

A stainless steel backbone,

glossy marble finishes,

and titanium security net

to keep the plebs from climbing up

and for the prodigal to englut

an eyeful of birds of paradise

and twangy city symphony.

Waiting, far below the placid chitter

outside the emerald glass, a rumbling

splits the grimy bottom parched

too long. The greedy pirate,

cut by shattered ceilings, loses

his head. It rolls like a coconut

and spills a sweet nectar below.

his coffee. A fetid scent

of sago palm fronds billows

upwards to rattan-latticed frieze,

a wispy lick of the facade

of animist caricatures. The cannibal muses

as the purr of Kopi Luwak settles,

steeped in carrion-coated deals and

polyglot grunts and grumbles

from the electric donut.

Human flesh differs naught from pig

when raised to a green empyrean

nestled on thirsty cement roots

crust with salted grime.

A stainless steel backbone,

glossy marble finishes,

and titanium security net

to keep the plebs from climbing up

and for the prodigal to englut

an eyeful of birds of paradise

and twangy city symphony.

Waiting, far below the placid chitter

outside the emerald glass, a rumbling

splits the grimy bottom parched

too long. The greedy pirate,

cut by shattered ceilings, loses

his head. It rolls like a coconut

and spills a sweet nectar below.

A Dedication to Remembrance

A long day passing

Passing by like the precious final breath of waking life

Before the soul succumbs to sleep, I lay and wonder

How much of the ethereal being is embodied by the consciousness

And how much beyond

If erasing blocks of memories will change the person now

If memory was temporal like a breath but still I fill in the inconsistencies and missing spaces

I lay and wonder if, like a soft polymer tablet, something organic is altered

With each impressionable encounter

Now

I can never if desired be the same again

Even if the memories fade or expire

When we meet again

By chance encounter

Before the soul succumbs to sleep, I lay and wonder

A different time

A different place

Was it through fortune

I came to know you

Or was it something

Much beyond

Waking life

And how much beyond

When we meet

Again

A long day

Passing

Passing by like the precious final breath of waking life

Before the soul succumbs to sleep, I lay and wonder

How much of the ethereal being is embodied by the consciousness

And how much beyond

If erasing blocks of memories will change the person now

If memory was temporal like a breath but still I fill in the inconsistencies and missing spaces

I lay and wonder if, like a soft polymer tablet, something organic is altered

With each impressionable encounter

Now

I can never if desired be the same again

Even if the memories fade or expire

When we meet again

By chance encounter

Before the soul succumbs to sleep, I lay and wonder

A different time

A different place

Was it through fortune

I came to know you

Or was it something

Much beyond

Waking life

And how much beyond

When we meet

Again

A long day

Passing

A Morning Ode to that Sanguine Thirst

A sordid lust affair last night has chilled,

Prolonged my morning, yet the glory lacked.

Exorbitant indulgences are billed

By eyes locked like dark blinds I mildly cracked.

Deep in nostalgia’s lapse, a wont to call

Her sanguine taste rose up again.

Yet, curt its interruption by the crawl

Up---my throat now clumped as wetted sand.

The rosy warmth, the cheeks I grasped last night

Is lost. How aptly I was crowned the fool!

A face once mirth-filled ‘surped by one to fright

And lips that mingled with her nectar drool.

Again I'll dine with she, so noxious for

My health. Yet, supple is the song she pours.

Prolonged my morning, yet the glory lacked.

Exorbitant indulgences are billed

By eyes locked like dark blinds I mildly cracked.

Deep in nostalgia’s lapse, a wont to call

Her sanguine taste rose up again.

Yet, curt its interruption by the crawl

Up---my throat now clumped as wetted sand.

The rosy warmth, the cheeks I grasped last night

Is lost. How aptly I was crowned the fool!

A face once mirth-filled ‘surped by one to fright

And lips that mingled with her nectar drool.

Again I'll dine with she, so noxious for

My health. Yet, supple is the song she pours.

Gentlemen Prefer Blonds, or at least Politicians and Killers do in “Blow Out”

Made as a neo-noir derivative of Michelangelo Antonioni’s “Blowup”, Brian De Palma’s “Blow Out” satisfies fans of his psychological thrillers with an edgy thematic scheme of sound technics. The title “Blow Out” is a double entendre for the burst of a tire and the result of sending too much power to speakers that kill the sound and not, unfortunately, the hairstyle trend known as the “Brooklyn Fade”. Of the foppish hairstyles donned in Grease and Saturday Night Fever, John Travolta will grace us no more but blonds aplenty we do have.

The film opens with a ‘movie within a movie’, a B-level horror film that pays homage to “Black Christmas.” The story involves a serial killer who peers through windows of a sorority house in voyeuristic point of view shots. The production is stymied at a shower scene that directly alludes to "Psycho" when the busty blond is unable to deliver a “decent” blood-curdling scream. It’s a chuckler when, ipso facto, Vivian Leigh's screams in “Psycho” are dubbed over by a staccato of shrieky violins. Jack the sound technician (John Travolta) sets out to find a girl with the perfect scream to dub over the more pitiful attempts. (The character director, Jack Terry, should have used cold water.) De Palma’s crude humor never fails to make its appearance with Jack Terry remarking, “I didn’t hire her for her scream, Jack, I hired her for her tits!”

During Jack’s night out dilly-dallying with the frogs and the owls in a park, he falls privy to witnessing (and subsequently recording) a car crash involving a governor and his mistress Sally (Nancy Allen). With his suspicions piqued after a “friend” of the governor implores Jack’s silence over existence of the mistress he saves, he replays the sounds of the incident and discovers that the governor was actually murdered.

Although posters of B-horrors are plastered all throughout Jack’s studio, Brian de Palma lifts “Blow Out” from the inferior realm of the B-horror with his uncanny reinterpretation of Hitchcock’s camera techniques and neurotic fascination with bomb-shell blonds who are not as they ostensibly appear. Of his ostentatious camera tricks, his long 360 degree pan gives the zoom out, track in shot from “Vertigo” a run for one of the most bewildering camera effects. Imagine being more confused than Woody Allen as Miles in “Sleeper” when entangled in hundreds of feet of tape reel. With the use of saturated filters of blues, yellows, and especially reds draped by dark shadows, this neo-noir feels as menacing and sleazy as it can get. Throw down the uncomfortably close character and object close-ups and camera pans over room ceilings and through objects and you feel as unsettled and trapped as Jodie Foster's character in David Fincher’s “Panic Room”.

Among his nifty bag of camera tricks with canted angles, tight framing, split screens, wide-angle lens, and voyeuristic over-the-shoulder tracking shots, his prestidigitation with sound is akin to Robert Bresson manipulation of sound in “A Man Escaped.” A heightened sensitivity to sound effects aids the main character's great escape from prison and subsequent execution. In the case of “Blow Out”, Jack relies on a wired-tape recorder attached to Sally to keep the killer from claiming his final target.

While you never feel alone with Jack and Sally with the constant activity, mirrors, or photographs of people in the background, as Jack states, “I wish you only had to worry about me”, people and things are also not as they appear. Sally, as a make-up artist, describes playfully how her face is not as natural as it seems. The governor’s associates successfully cover up for the debased governor who was framed in a sex-scandal with Sally. The dirty cops Jake entrapped, by hook and by crook, in his previous wired-tape gigs with the police were affiliated with the mob. John Lithgow, as Burke the killer, masks his fatal plan for Sally with a pseudo-sex killing spree like the Sunset Strip Murders. Paint the town in red herrings, and shades when a young blond is to be murdered, and agitate not only figurative bulls but the audience as well.

Warnings of foreboding such as the paralleled murders of the cop who died as a result of Jake’s failed wired-tape attempt and the second blond prostitute suggest that Sally is likely to be murdered. The shocker comes from the realization that several moments in the film allude to John F. Kennedy's assassination. There were connotative conjectures about the governor, such as the exclamation “that man was going to be our next president”. The hidden gunman targeting the governor’s vehicle, the affair with a blond, and the political innuendos of the Liberty Bell celebrations were all one extended parable for John F. Kennedy’s assassination.

Within the spectacular display of De Palma's cinematic tricks and allegories, the scene with the fireworks is probably the one blot on the landscape. Yet, the way De Palma wraps up this blood-and-thunder romance with Jack’s eventual recording of the perfect scream renders it all but forgotten in the end.

The film opens with a ‘movie within a movie’, a B-level horror film that pays homage to “Black Christmas.” The story involves a serial killer who peers through windows of a sorority house in voyeuristic point of view shots. The production is stymied at a shower scene that directly alludes to "Psycho" when the busty blond is unable to deliver a “decent” blood-curdling scream. It’s a chuckler when, ipso facto, Vivian Leigh's screams in “Psycho” are dubbed over by a staccato of shrieky violins. Jack the sound technician (John Travolta) sets out to find a girl with the perfect scream to dub over the more pitiful attempts. (The character director, Jack Terry, should have used cold water.) De Palma’s crude humor never fails to make its appearance with Jack Terry remarking, “I didn’t hire her for her scream, Jack, I hired her for her tits!”

During Jack’s night out dilly-dallying with the frogs and the owls in a park, he falls privy to witnessing (and subsequently recording) a car crash involving a governor and his mistress Sally (Nancy Allen). With his suspicions piqued after a “friend” of the governor implores Jack’s silence over existence of the mistress he saves, he replays the sounds of the incident and discovers that the governor was actually murdered.

Although posters of B-horrors are plastered all throughout Jack’s studio, Brian de Palma lifts “Blow Out” from the inferior realm of the B-horror with his uncanny reinterpretation of Hitchcock’s camera techniques and neurotic fascination with bomb-shell blonds who are not as they ostensibly appear. Of his ostentatious camera tricks, his long 360 degree pan gives the zoom out, track in shot from “Vertigo” a run for one of the most bewildering camera effects. Imagine being more confused than Woody Allen as Miles in “Sleeper” when entangled in hundreds of feet of tape reel. With the use of saturated filters of blues, yellows, and especially reds draped by dark shadows, this neo-noir feels as menacing and sleazy as it can get. Throw down the uncomfortably close character and object close-ups and camera pans over room ceilings and through objects and you feel as unsettled and trapped as Jodie Foster's character in David Fincher’s “Panic Room”.

Among his nifty bag of camera tricks with canted angles, tight framing, split screens, wide-angle lens, and voyeuristic over-the-shoulder tracking shots, his prestidigitation with sound is akin to Robert Bresson manipulation of sound in “A Man Escaped.” A heightened sensitivity to sound effects aids the main character's great escape from prison and subsequent execution. In the case of “Blow Out”, Jack relies on a wired-tape recorder attached to Sally to keep the killer from claiming his final target.

While you never feel alone with Jack and Sally with the constant activity, mirrors, or photographs of people in the background, as Jack states, “I wish you only had to worry about me”, people and things are also not as they appear. Sally, as a make-up artist, describes playfully how her face is not as natural as it seems. The governor’s associates successfully cover up for the debased governor who was framed in a sex-scandal with Sally. The dirty cops Jake entrapped, by hook and by crook, in his previous wired-tape gigs with the police were affiliated with the mob. John Lithgow, as Burke the killer, masks his fatal plan for Sally with a pseudo-sex killing spree like the Sunset Strip Murders. Paint the town in red herrings, and shades when a young blond is to be murdered, and agitate not only figurative bulls but the audience as well.

Warnings of foreboding such as the paralleled murders of the cop who died as a result of Jake’s failed wired-tape attempt and the second blond prostitute suggest that Sally is likely to be murdered. The shocker comes from the realization that several moments in the film allude to John F. Kennedy's assassination. There were connotative conjectures about the governor, such as the exclamation “that man was going to be our next president”. The hidden gunman targeting the governor’s vehicle, the affair with a blond, and the political innuendos of the Liberty Bell celebrations were all one extended parable for John F. Kennedy’s assassination.

Within the spectacular display of De Palma's cinematic tricks and allegories, the scene with the fireworks is probably the one blot on the landscape. Yet, the way De Palma wraps up this blood-and-thunder romance with Jack’s eventual recording of the perfect scream renders it all but forgotten in the end.

Gus Van Sant's Milk: We Recruit You!

In my anticipation for Gus Van Sant's Milk, I was most curious about the framing style Van Sant employed in his flashback depiction of Harvey Milk’s life and work as both a biopic and as a period film, capturing the salient events and cultural atmosphere of Castro Street and the San Francisco area during the 1970s. Van Sant often tailored his use of camera angles and shots, among other cinematographic tools across his films, in a far more experimental manner than the Hollywood blockbuster to enhance his films' effectiveness conveying the mood and meaning within his settings. His chilling tracking shots that stalked the Columbine-like students in Elephant and the persistent use of distant long-shots, and minimal facial exposure, of the isolated Kurt Cobain character in Last Days represent only a few of his great stylistic devices.

I was pleased by Van Sant’s determination to focus less on the psychological dynamics operating behind Milk’s character in face of great adversity (especially as an allegory for the psychological disintegration common of homosexual characters in Hollywood’s past e.g. Plato in Rebel Without a Cause) for more in-depth focus on the feel and effect of Milk’s role in the gay movement in San Francisco. His greater dedication to the “period film” aspect, and most definitely his juxtaposition of real-life clips of Milk and the gay community, specified the target of the emotional drive of the film. I was brought to tears not so much due to an unearthing of memories of my encounters with anti-gay/bi hostilities but as a result of finally seeing a laudable biopic made the way it should.

It’s great that Van Sant “recruits” us along to remind us how real these events were by (1) positioning our point of view as another protestor within the greater mass in Milk’s rallies and (2) by initially confining his setting inside Castro Street before gradually expanding our exposure (through news broadcasts and such) to the far-reaching effects of and retaliation to the gay movement as he rises to “Mayor of Castro Street.” However, the film’s greatest emotional drive emanated from his humanization of Milk with the voyeuristic shots infringing on the privacy of Milk’s home affairs and Milk’s acrophobic point-of-view shots while he faced a seemingly endless crowd before giving one of his greatest speeches (especially with potential killers in the mass).

Reminiscent of Orson Welles’ style, Van Sant utilized a number of “artsy” metaphoric images to illustrate the disenchantment associated with the pessimistic reality for homosexuals in America. In the scene in which a young homosexual man was murdered in the streets, Van Sant portrayed a close-up reflection of cops surrounding the bloody incident on a side of a whistle dropped on the cement road, possibly belonging to the murdered man. Immediately before, homosexuals recruited to Milk’s cause discussed how it was necessary for them to carry their own whistles so they can protect each other from hate-violence. The police force has not only neglected their victimization but was even suggested to have participated. The irony lies in the traditional icon of the “whistle” representing the “whistle-blowing” role of justice, what the police force should have represented. Just as we are provided a glimpse of Charles Kane’s tragic moment of lost innocence with the object close-up shot of the “Rosebud” in the snow-globe, the whistle serves a similar role for our justice system’s tragic moment of lost innocence.

At the moment Dan White runs through a series of office doorways to assassinate Milk, the Citizen Kane homage is undeniable if we recall Kane running through the many doorways of his gloomy mansion to his second wife’s room and we realize that it was Susan Alexander’s desertion that becomes the final catalyst for his demise and ultimate death. Van Sant perhaps refers to a deeper analogy since these are the walls of a law-making body. We see that the legal system represent a false sense of security that is inefficient in stopping the destructive impulses of hatred on its war-path. This is especially true when the law-enforcement system meters out trivial sentences in proportion to the maliciousness of the crime.

Despite grim images of the diminished efficacy of government, Van Sant provides allegoric reminders of hope with the handicapped mystery caller from Minnesota and the politically-disinterested prostitute, Cleve Jones, he later recruited. The use of Judy Garland’s signature song “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” from Wizard of Oz during a civil rights march may, at first impressions, appear to be a fall-back to a clichéd homosexual motif. However, considering the implications of Milk’s martyred figure in this, even up to today, ongoing gay civil rights movement, it is emotionally on-point and embodies the long journey gay rights activists have to make far from home.

In light of the heavy political and religious polemical discourse, especially with the recent passage of Proposition 8 in California, Van Sant left ample room for, not surprisingly, the gay jokes. Although I was slightly put-off by the “cake-eater” and “gay-recruiter” allusions, I was delighted by the mise-en-scene with Harvey and Scott making out in public beside the “Come In, We’re Open” sign in front of their store and the inclusion of the ultra-feminine ditsy Latin Lover/Housewife stereotype not dissimilar to Robin William’s “mistress/maid” Agador from The Birdcage. Of course, this is not including the dialogued humor!

As much as these gay stereotypes may irritate, as any use of categorical assumptions about gay character, they provide a breathy relief to memories of repressive Hollywood years before the 1960s or so when any reference to homosexuality had to be subtly and symbolically incorporated into the script (e.g. Alfred Hitchcock’s Rope about gay serial killers Leopold and Loeb) or any suggestively homosexual characters were depicted as sissy, mentally unstable, or suicidally depressed (e.g. Tom Lee’s character in Vincente Minnelli’s adaptation of the play Tea and Sympathy). As a note, I found the documentary The Celluloid Closet by Rob Epstein particularly useful in understanding the chronological montage of gay film.

Later on, Van Sant even sneaks in some fan service when he self-quotes Elephant: the scene where the camera performs a rotating scan across Milk’s circle of campaign workers in an office alludes directly to the student discussion circle covering the subject of homosexuality in Watt High School. Whereas then you, the viewer, were challenged to pick out which of the students in the circle were gay but had not come out, this time the irony lies in the fact that all of Milk’s campaign recruits were openly gay. There is no necessity for a “witch-hunt” this time.

While the audience is dolefully aware of Harvey Milk’s impending murder, given the historic precedent, Van Sant provides a hopeful “moral” behind Milk’s death as a positive alterative to the disheartening and all-too familiar plot-ending of many gay-innuendo’ed films in the past. The tragic deaths of the homosexual character often appeared to be penitence for their “sin” (not considering films where the homosexual character is converted or assimilated into straight society yet that in itself is “death”). Along with the legacy left behind, epitomized by the crowd of mourners that held lit candles on Castro Street, Milk’s final dying moment with his body faced towards the opera hall represents redemption for his love for Scott, which he was unable to enjoy in this life due to his dedication to the gay rights movement, and his soul (for of course the greater, universal sin).

I was pleased by Van Sant’s determination to focus less on the psychological dynamics operating behind Milk’s character in face of great adversity (especially as an allegory for the psychological disintegration common of homosexual characters in Hollywood’s past e.g. Plato in Rebel Without a Cause) for more in-depth focus on the feel and effect of Milk’s role in the gay movement in San Francisco. His greater dedication to the “period film” aspect, and most definitely his juxtaposition of real-life clips of Milk and the gay community, specified the target of the emotional drive of the film. I was brought to tears not so much due to an unearthing of memories of my encounters with anti-gay/bi hostilities but as a result of finally seeing a laudable biopic made the way it should.

It’s great that Van Sant “recruits” us along to remind us how real these events were by (1) positioning our point of view as another protestor within the greater mass in Milk’s rallies and (2) by initially confining his setting inside Castro Street before gradually expanding our exposure (through news broadcasts and such) to the far-reaching effects of and retaliation to the gay movement as he rises to “Mayor of Castro Street.” However, the film’s greatest emotional drive emanated from his humanization of Milk with the voyeuristic shots infringing on the privacy of Milk’s home affairs and Milk’s acrophobic point-of-view shots while he faced a seemingly endless crowd before giving one of his greatest speeches (especially with potential killers in the mass).

Reminiscent of Orson Welles’ style, Van Sant utilized a number of “artsy” metaphoric images to illustrate the disenchantment associated with the pessimistic reality for homosexuals in America. In the scene in which a young homosexual man was murdered in the streets, Van Sant portrayed a close-up reflection of cops surrounding the bloody incident on a side of a whistle dropped on the cement road, possibly belonging to the murdered man. Immediately before, homosexuals recruited to Milk’s cause discussed how it was necessary for them to carry their own whistles so they can protect each other from hate-violence. The police force has not only neglected their victimization but was even suggested to have participated. The irony lies in the traditional icon of the “whistle” representing the “whistle-blowing” role of justice, what the police force should have represented. Just as we are provided a glimpse of Charles Kane’s tragic moment of lost innocence with the object close-up shot of the “Rosebud” in the snow-globe, the whistle serves a similar role for our justice system’s tragic moment of lost innocence.

At the moment Dan White runs through a series of office doorways to assassinate Milk, the Citizen Kane homage is undeniable if we recall Kane running through the many doorways of his gloomy mansion to his second wife’s room and we realize that it was Susan Alexander’s desertion that becomes the final catalyst for his demise and ultimate death. Van Sant perhaps refers to a deeper analogy since these are the walls of a law-making body. We see that the legal system represent a false sense of security that is inefficient in stopping the destructive impulses of hatred on its war-path. This is especially true when the law-enforcement system meters out trivial sentences in proportion to the maliciousness of the crime.

Despite grim images of the diminished efficacy of government, Van Sant provides allegoric reminders of hope with the handicapped mystery caller from Minnesota and the politically-disinterested prostitute, Cleve Jones, he later recruited. The use of Judy Garland’s signature song “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” from Wizard of Oz during a civil rights march may, at first impressions, appear to be a fall-back to a clichéd homosexual motif. However, considering the implications of Milk’s martyred figure in this, even up to today, ongoing gay civil rights movement, it is emotionally on-point and embodies the long journey gay rights activists have to make far from home.

In light of the heavy political and religious polemical discourse, especially with the recent passage of Proposition 8 in California, Van Sant left ample room for, not surprisingly, the gay jokes. Although I was slightly put-off by the “cake-eater” and “gay-recruiter” allusions, I was delighted by the mise-en-scene with Harvey and Scott making out in public beside the “Come In, We’re Open” sign in front of their store and the inclusion of the ultra-feminine ditsy Latin Lover/Housewife stereotype not dissimilar to Robin William’s “mistress/maid” Agador from The Birdcage. Of course, this is not including the dialogued humor!

As much as these gay stereotypes may irritate, as any use of categorical assumptions about gay character, they provide a breathy relief to memories of repressive Hollywood years before the 1960s or so when any reference to homosexuality had to be subtly and symbolically incorporated into the script (e.g. Alfred Hitchcock’s Rope about gay serial killers Leopold and Loeb) or any suggestively homosexual characters were depicted as sissy, mentally unstable, or suicidally depressed (e.g. Tom Lee’s character in Vincente Minnelli’s adaptation of the play Tea and Sympathy). As a note, I found the documentary The Celluloid Closet by Rob Epstein particularly useful in understanding the chronological montage of gay film.

Later on, Van Sant even sneaks in some fan service when he self-quotes Elephant: the scene where the camera performs a rotating scan across Milk’s circle of campaign workers in an office alludes directly to the student discussion circle covering the subject of homosexuality in Watt High School. Whereas then you, the viewer, were challenged to pick out which of the students in the circle were gay but had not come out, this time the irony lies in the fact that all of Milk’s campaign recruits were openly gay. There is no necessity for a “witch-hunt” this time.

While the audience is dolefully aware of Harvey Milk’s impending murder, given the historic precedent, Van Sant provides a hopeful “moral” behind Milk’s death as a positive alterative to the disheartening and all-too familiar plot-ending of many gay-innuendo’ed films in the past. The tragic deaths of the homosexual character often appeared to be penitence for their “sin” (not considering films where the homosexual character is converted or assimilated into straight society yet that in itself is “death”). Along with the legacy left behind, epitomized by the crowd of mourners that held lit candles on Castro Street, Milk’s final dying moment with his body faced towards the opera hall represents redemption for his love for Scott, which he was unable to enjoy in this life due to his dedication to the gay rights movement, and his soul (for of course the greater, universal sin).

Tampopo: A Post-Modern Feast

During the late 1980s and 1990s, directors such as Takeshi Kitano and Morita Yoshimitsu created films defined by minimalistic emotions, music, dialogue, and such in a “detached style.” These films engaged in discourses that criticize contemporary Japanese society and suggest that film is not capable of showing “truth” but exists only as “film” itself. As Linda Ehrlich notes, Tampopo is also a critical film that “joins a celebration of the cinema in a ‘comedy of manners’ about Japanese society.” Itami Juzo’s Tampopo participates in post-modern film discourse (due to its fragmented, “renga-like” narrative form, its violation of the fourth wall, and its absurd portrayal of Japanese rules and manners) but also offers a pastiche celebration of film with its anacreontic excess of homage, clichés, emotional music, dramatic dialogue and other aspects of traditional Hollywood cinema. Tampopo represents an absurd parallelism of the rules for making and loving food, sex, and film.

The implicit meaning of the train and cowboy motifs in Tampopo must be deconstructed to better understand the ways Tampopo break the rules of narrative continuity. Withstanding the plot setup, the story of Tampopo’s achievement follows Classic Hollywood Cinema conventions with Tampopo, Goro, and her circle of male guides as casual agents that direct the narrative from point A to point B, in which she overcomes obstacles to reach her defined goal. With the help of Goro and her other new friends, Tampopo changes from a widowed, disheveled mother of a bullied child and heiress to an unkempt ramen house into a successful, intelligent, and happy owner of “Tampopo’s Ramen” within a competitive noodle market.

A passing train appears multiple times in the background throughout the film. The passing train could embody referential meaning for one of the greatest monumental moments in film history. The Great Train Robbery from 1903 was the first narrative film directed by Edwin S. Porter. In the context of Tampopo, however, the passage of the train from its starting point to its destination parallels the structural progression of the film narrative from point A to point B and the act of eating and sex, which were common, juxtaposed themes. In the first vignette, the “ramen-eating master” says to the slice of beef, “I’ll see you later” as a funny nod to the inevitable path of the beef after consumption. In another scene, the camera tracks the entry of a piece of food into a character’s mouth before there is an immediate cut to a passing train. Finally, the passage of trains was often used as a joke reference to the act of sex in films.

Donning the iconic hat from the “Old West” and occasionally accompanied by non-diegetic music characteristic of most Westerns, Goro is introduced as the cowboy. The nature of the cowboy, by profession, is to direct the transport of large herds from one location to another, point A to B. In the same way Goro directs Tampopo, the helpless and pathetic protagonist, to become a great female noodle-maker by collecting the best traits of successful noodle houses in her vicinity, this film director creates a sort of “compilation film” that pays homage to Westerns such as High Noon, Giant, The Searchers, The Wild Bunch, and Once Upon a Time in the West while also uses clichés from other genres such as tragedy, romance, and comedy. The irony of the cowboy lies in his anachronism. During times when Americans still lauded the idea of Manifest Destiny, the respective setting of the cowboy, cowboys represented the trespassing of new terrain. Now, all the land in America has been infringed upon and claimed and cowboys were replaced by more powerful mechanisms of transport such as trains. Just as the cowboy serves as an allegory for nostalgia for a dead time period, Tampopo is an allegory for the end of the modern film era when film was still capable of speaking for itself.

Juzo positions Tampopo in post-modernist film categories when he juxtaposes its linear narrative form with multiple vignettes that hover between being diegetic and non-diegetic inserts and the non-diegetic yakuza character that breaks the fourth wall. The yakuza directly addresses the audience in the first scene and stars in his own separate story within the main plot. His character serves to break the narrative continuity, interrupting the audiences’ passive enjoyment of the main story. The vignettes are short stories in some relation to Tampopo’s life, featuring the point of views of secondary characters. By sharply criticizing Japanese cultural and social norms, they contribute to the themes of food and teaching rules. Public and private places of dining are common grounds for rules and customs in Japanese culture, as it is in many cultures. Here, they become spectacles for the exposure of hypocrisy, triviality, and absurdity. The first short clip consists of a young man’s flashback memories of his master eating noodles the “proper” way, following many non-sensible and non-pragmatic rules. Another clip illustrates a young amateur-looking businessman out of six demonstrating his sophisticated, informed knowledge of French cuisine to the outrage and embarrassment of the older businessmen (who all order the same, boring meal). Another vignette shows a refined Japanese woman giving instructions to other ladies on how to eat noodles quietly while a Western man slurps his noodle loudly and disgustingly in the vicinity. Then all the women, including her, follow suit despite her repeated instructions on proper table manners. In a way, Goro and Tampopo’s proclaimed measure of a successful noodle house, in which the customers finish up to the last drop of soup from their bowls, is as shallow as the rules the film criticizes. In an analogy to film appreciation, this suggests that if a customer in a movie theatre sits through an entire movie, to the point when credits begin rolling, the film is considered good. The customer in a noodle house or movie theatre could merely be satisfying their “natural cravings” for noodles or a movie for that moment.

The yakuza character and his lovely girlfriend introduced in the first scene represent the “intrusion” to the narrative and editing continuity that serves not to add to the narrative but detract from it in a critical manner characteristic of post-modern films. Right at the beginning, the yakuza questions the audience, “...so you’re in the movie too”. Then, the yakuza acknowledges his own ironic role when he states that for “a man’s last movie”, he didn’t want interruptions such as alarms going off in the theatre whereas he himself is an interruption to the film. The yakuza repeats that Tampopo will be his last movie a few times before he is finally shot near the end of the film. His only role in Tampopo is to watch the main story before he is killed off. Just as he exists for the audience to observe his dramatic death, Tampopo exists to mark off the death or end of the modern period of film-making. Tampopo consists of not much more than a pastiche of clichés and homage. The same way Tampopo’s successful noodle house is a testament to how a collage of many of the best features of good restaurants can create a great one, Tampopo seeks to represent a similar amalgamation that is pseudo-new but offers no inherent truth in its main story.

Although Tampopo may not have any significant implicit or explicit “morals” or “meanings’ to the story, it still represents a celebration of cinema for its own sake. Throughout the film, the audience is bombarded with scenes of people giving into their natural hunger and sex drives in a sort of anti-intellectual atmosphere. The yakuza and his beautiful lover dine on fine cuisine from the first scene to the sex scenes. Even in his final monologue, he provides elaborate descriptions for making delicious pork sausages. The yakuza also lustily sucks from an oyster collected by a young girl on the beach, and then her fingers, and finally her lips. In a vignette, a man with an ice cream cone offers his ice cream to a young boy despite the prohibition on unnatural foods indicated on the sign tied around the boy’s neck. The boy, in reaction to the ice cream, devours it greedily and happily. In another vignette, an old woman giddily takes pleasure in poking food throughout the supermarket before she is swatted by the clerk. The closing scene features a mother unabashedly breastfeeding her child on a park bench. In the last few vignettes mentioned, the film not only encourages indulgence in pleasure but also acknowledges an element of “guilt” that is haughtily cast aside. The execution of the yakuza, who committed the cinematic crime of breaking the fourth wall, could represent the first cathartic release for the audience. The viewers can finally enjoy the primary story without any distractions. In many post-modernist films, directors often employ various techniques to break the audience’s complete attention as a reminder of their actual voyeuristic position and that they are just observing a film separate from their reality. Tampopo’s complete triumph over her pathetic beginnings and various obstacles along the way, which brings the film to a strong closure, represents the second cathartic release. Regardless of the fact that Tampopo is nothing more than an amalgamation of clichés and homage, Itami Juzo still wraps up the narrative with a Hollywood ending. Contemporary viewers know better than to be content with the typical Hollywood ending but Itami Juzo acknowledges that “guilty” pleasure associated with such traditions of cinema for its own sake.

In the same way people enjoy taking trips to escape to or explore new places by way of various vehicles of transportation such as trains, Itami Juzo encourages his audience to go along for the ride with Tampopo. Although Tampopo exhibits the semblance of the typical Hollywood linear narrative structure, Juzo inserts many vignettes with some connection to the main themes and breaks the fourth wall with the yakuza character. These elements of the film signify that Tampopo really belongs in post-modern film categories yet is still capable of celebrating film as a great artistic medium despite critical modern sensibilities.

The implicit meaning of the train and cowboy motifs in Tampopo must be deconstructed to better understand the ways Tampopo break the rules of narrative continuity. Withstanding the plot setup, the story of Tampopo’s achievement follows Classic Hollywood Cinema conventions with Tampopo, Goro, and her circle of male guides as casual agents that direct the narrative from point A to point B, in which she overcomes obstacles to reach her defined goal. With the help of Goro and her other new friends, Tampopo changes from a widowed, disheveled mother of a bullied child and heiress to an unkempt ramen house into a successful, intelligent, and happy owner of “Tampopo’s Ramen” within a competitive noodle market.

A passing train appears multiple times in the background throughout the film. The passing train could embody referential meaning for one of the greatest monumental moments in film history. The Great Train Robbery from 1903 was the first narrative film directed by Edwin S. Porter. In the context of Tampopo, however, the passage of the train from its starting point to its destination parallels the structural progression of the film narrative from point A to point B and the act of eating and sex, which were common, juxtaposed themes. In the first vignette, the “ramen-eating master” says to the slice of beef, “I’ll see you later” as a funny nod to the inevitable path of the beef after consumption. In another scene, the camera tracks the entry of a piece of food into a character’s mouth before there is an immediate cut to a passing train. Finally, the passage of trains was often used as a joke reference to the act of sex in films.

Donning the iconic hat from the “Old West” and occasionally accompanied by non-diegetic music characteristic of most Westerns, Goro is introduced as the cowboy. The nature of the cowboy, by profession, is to direct the transport of large herds from one location to another, point A to B. In the same way Goro directs Tampopo, the helpless and pathetic protagonist, to become a great female noodle-maker by collecting the best traits of successful noodle houses in her vicinity, this film director creates a sort of “compilation film” that pays homage to Westerns such as High Noon, Giant, The Searchers, The Wild Bunch, and Once Upon a Time in the West while also uses clichés from other genres such as tragedy, romance, and comedy. The irony of the cowboy lies in his anachronism. During times when Americans still lauded the idea of Manifest Destiny, the respective setting of the cowboy, cowboys represented the trespassing of new terrain. Now, all the land in America has been infringed upon and claimed and cowboys were replaced by more powerful mechanisms of transport such as trains. Just as the cowboy serves as an allegory for nostalgia for a dead time period, Tampopo is an allegory for the end of the modern film era when film was still capable of speaking for itself.

Juzo positions Tampopo in post-modernist film categories when he juxtaposes its linear narrative form with multiple vignettes that hover between being diegetic and non-diegetic inserts and the non-diegetic yakuza character that breaks the fourth wall. The yakuza directly addresses the audience in the first scene and stars in his own separate story within the main plot. His character serves to break the narrative continuity, interrupting the audiences’ passive enjoyment of the main story. The vignettes are short stories in some relation to Tampopo’s life, featuring the point of views of secondary characters. By sharply criticizing Japanese cultural and social norms, they contribute to the themes of food and teaching rules. Public and private places of dining are common grounds for rules and customs in Japanese culture, as it is in many cultures. Here, they become spectacles for the exposure of hypocrisy, triviality, and absurdity. The first short clip consists of a young man’s flashback memories of his master eating noodles the “proper” way, following many non-sensible and non-pragmatic rules. Another clip illustrates a young amateur-looking businessman out of six demonstrating his sophisticated, informed knowledge of French cuisine to the outrage and embarrassment of the older businessmen (who all order the same, boring meal). Another vignette shows a refined Japanese woman giving instructions to other ladies on how to eat noodles quietly while a Western man slurps his noodle loudly and disgustingly in the vicinity. Then all the women, including her, follow suit despite her repeated instructions on proper table manners. In a way, Goro and Tampopo’s proclaimed measure of a successful noodle house, in which the customers finish up to the last drop of soup from their bowls, is as shallow as the rules the film criticizes. In an analogy to film appreciation, this suggests that if a customer in a movie theatre sits through an entire movie, to the point when credits begin rolling, the film is considered good. The customer in a noodle house or movie theatre could merely be satisfying their “natural cravings” for noodles or a movie for that moment.

The yakuza character and his lovely girlfriend introduced in the first scene represent the “intrusion” to the narrative and editing continuity that serves not to add to the narrative but detract from it in a critical manner characteristic of post-modern films. Right at the beginning, the yakuza questions the audience, “...so you’re in the movie too”. Then, the yakuza acknowledges his own ironic role when he states that for “a man’s last movie”, he didn’t want interruptions such as alarms going off in the theatre whereas he himself is an interruption to the film. The yakuza repeats that Tampopo will be his last movie a few times before he is finally shot near the end of the film. His only role in Tampopo is to watch the main story before he is killed off. Just as he exists for the audience to observe his dramatic death, Tampopo exists to mark off the death or end of the modern period of film-making. Tampopo consists of not much more than a pastiche of clichés and homage. The same way Tampopo’s successful noodle house is a testament to how a collage of many of the best features of good restaurants can create a great one, Tampopo seeks to represent a similar amalgamation that is pseudo-new but offers no inherent truth in its main story.

Although Tampopo may not have any significant implicit or explicit “morals” or “meanings’ to the story, it still represents a celebration of cinema for its own sake. Throughout the film, the audience is bombarded with scenes of people giving into their natural hunger and sex drives in a sort of anti-intellectual atmosphere. The yakuza and his beautiful lover dine on fine cuisine from the first scene to the sex scenes. Even in his final monologue, he provides elaborate descriptions for making delicious pork sausages. The yakuza also lustily sucks from an oyster collected by a young girl on the beach, and then her fingers, and finally her lips. In a vignette, a man with an ice cream cone offers his ice cream to a young boy despite the prohibition on unnatural foods indicated on the sign tied around the boy’s neck. The boy, in reaction to the ice cream, devours it greedily and happily. In another vignette, an old woman giddily takes pleasure in poking food throughout the supermarket before she is swatted by the clerk. The closing scene features a mother unabashedly breastfeeding her child on a park bench. In the last few vignettes mentioned, the film not only encourages indulgence in pleasure but also acknowledges an element of “guilt” that is haughtily cast aside. The execution of the yakuza, who committed the cinematic crime of breaking the fourth wall, could represent the first cathartic release for the audience. The viewers can finally enjoy the primary story without any distractions. In many post-modernist films, directors often employ various techniques to break the audience’s complete attention as a reminder of their actual voyeuristic position and that they are just observing a film separate from their reality. Tampopo’s complete triumph over her pathetic beginnings and various obstacles along the way, which brings the film to a strong closure, represents the second cathartic release. Regardless of the fact that Tampopo is nothing more than an amalgamation of clichés and homage, Itami Juzo still wraps up the narrative with a Hollywood ending. Contemporary viewers know better than to be content with the typical Hollywood ending but Itami Juzo acknowledges that “guilty” pleasure associated with such traditions of cinema for its own sake.

In the same way people enjoy taking trips to escape to or explore new places by way of various vehicles of transportation such as trains, Itami Juzo encourages his audience to go along for the ride with Tampopo. Although Tampopo exhibits the semblance of the typical Hollywood linear narrative structure, Juzo inserts many vignettes with some connection to the main themes and breaks the fourth wall with the yakuza character. These elements of the film signify that Tampopo really belongs in post-modern film categories yet is still capable of celebrating film as a great artistic medium despite critical modern sensibilities.

The Apple in His Eye

6am, a frenetic face rang.

Morning trudged over the horizon,

No longer permitted to nest

in the waning shadows,

I was compelled to follow.

Tumbling loosely to the washroom,

I did not meet a familiar

glass image

but did meet a voluptuous crimson apple

In place of a visage once kissed

by my father, my friends, my lovers.

Certain the last cords of slumber were cut,

I finger curiously these newfound curves.

Be it better if only I were able to see it?

And this orb betrays

cerebral poison,

For my mind never knew snow white

but bed nightly vanity fair.

Or the weighty sin Adam bit into?

And in this moment of Cartesian doubt,

I dance for not the Dream but the Demon.

Be it better if we all carried on our heads

our own fruity apparitions?

Then Hieronymus was never merely an artist

but a metaphysical seer,

And we all are readymade subjects

for Jung’s mural of the unconscious.

Casting lofty thoughts aside,

Shining the skin of this reddish complexion,

I climbed outside, anxiously

waiting for the world

to welcome me.

Drifting about, I met only disappointment

When others took less notice

than if I wore a new hat.

Until that day a stranger grabbed my face

and bit me.

His desire hung, shamelessly.

Morning trudged over the horizon,

No longer permitted to nest

in the waning shadows,

I was compelled to follow.

Tumbling loosely to the washroom,

I did not meet a familiar

glass image

but did meet a voluptuous crimson apple

In place of a visage once kissed

by my father, my friends, my lovers.

Certain the last cords of slumber were cut,

I finger curiously these newfound curves.

Be it better if only I were able to see it?

And this orb betrays

cerebral poison,

For my mind never knew snow white

but bed nightly vanity fair.

Or the weighty sin Adam bit into?

And in this moment of Cartesian doubt,

I dance for not the Dream but the Demon.

Be it better if we all carried on our heads

our own fruity apparitions?

Then Hieronymus was never merely an artist

but a metaphysical seer,

And we all are readymade subjects

for Jung’s mural of the unconscious.

Casting lofty thoughts aside,

Shining the skin of this reddish complexion,

I climbed outside, anxiously

waiting for the world

to welcome me.

Drifting about, I met only disappointment

When others took less notice

than if I wore a new hat.

Until that day a stranger grabbed my face

and bit me.

His desire hung, shamelessly.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)