For cult fans of Chuck Palahniuk’s self-destructive, freak protagonists, Diary provides the satisfactory quencher for bloodlust. Diary opens with a harrowing premise centered on the attempted-suicide of a contractor, Peter Wilmot, and the “disappearing” rooms in Waytansea (“Wait and See”) Island. The reader is introduced to three women--the elderly mother Grace, the haggardly wife Misty, and Tabitha, the daughter--torn by the imminent loss of their Peter, who lies comatose in the hospital, and the Wilmot family home. Palahniuk wastes no effort indulging sadistic fascinations. Coma be damned at Peter's beck and call, Misty Kleinman pushes broach pins through his skin while she reignites her passion for painting.

Misty, a hotel waitress and the hapless heir to the Wilmot family curse, records the destitute humiliations and mysterious headaches she endures in her coma diary with Peter. With expert graphologist, Angel Delaporte, she investigates Peter’s scrawled writings in a hidden room in the Wilmot home. In much the same way Matheson’s What Dreams May Come privileges a journal as the medium for communication between the dead and the living, Misty‘s diary and Peter’s wall scribbles guide the blighted lovers through Misty’s rise and fall from artistic apogee with none of the sweetness of Almodovar’s Talk to Her but all of the creepy revelations. The victimized women, yes including Grace and Tabitha, to whom we give condolences eventually betray graver motives that are not made clear until later.

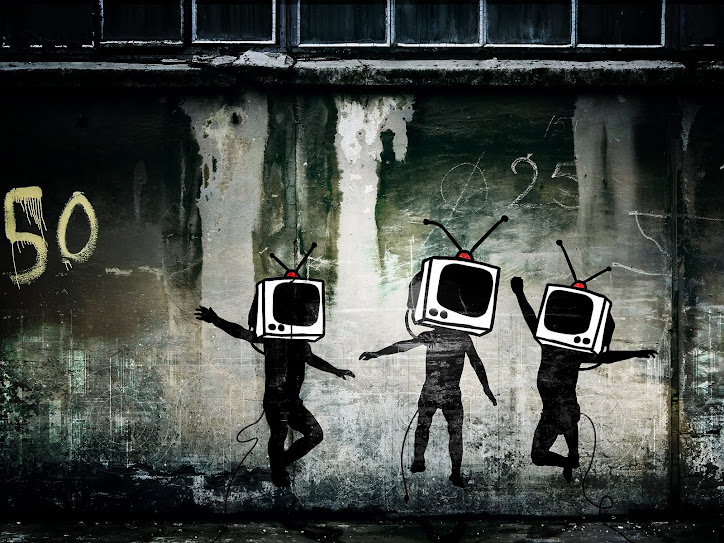

Palahniuk’s colloquial prose and steady pace sustains the reader through convoluted art lessons punctuated by nihilistic caveats of “what they didn’t teach you in art school.” Similarly with Haruki Murakami novels, Palaniuk makes the reader work, filtering through the metaphysical and psychological miasma. Then, the tragic hero's journey to discover, in every visceral sense of the word, cathartic release ends up severing her like a textbook Sybil. This trope, a shock ending that reveals an ego-centric verisimilitude that exists alongside a more tragic, repressed reality, was employed in a related manner with a narrator and his alter-ego in Fight Club. Yet, the realization of the doppelganger delivers a greater punch in the latter since in Fight Club the narrator and Tyler Durden co-existed for most of the story duration and is the penultimate big bang. By the time the reader is led through the gallery of horrific yet provocative caricatures and scenes, of which the narrator alternates beween the omniscient and Misty, the final chapters jerk like a rickety roller coaster with the gratuitous vomit and piss.

Just when the art schooling, for which Palahniuk clearly did his homework, sounds a bit like sententious prattle (about the sanctification of art and the necessary sacrifices), bodies fall and phantom figures appear. Misty trips and breaks her leg, Angel (who surprise, surprise was Peter's gay lover) is murdered, and her daughter supposedly drowns. Detective Stilton and Harrow Wilmot (Peter’s father) weave in and out of Misty’s fog of consciousness and Tabbi, quite literary and figuratively, leaves a blazing trail for Misty. The long anticipated denouement comes after the reader is made to trail many a squalid litter of Macguffins.

Misty’s paranoia explodes into a community-orchestrated conspiracy. Misty’s torments as a result of her artistic genius becomes the sacrificial offer fated to save Waytansea Island. The profound pause Palaniuk allows for paranormal eeriness behind the perfect angles and curves of Misty’s paintings and the exact depiction of the never-before-seen Hershel Burke chair, perhaps a nod to Vincent Van Gogh’s Chair, is effective. The schizophrenic jumble of epiphanies and frenetic pace that mirrors Misty’s mental disintegration is a questionable literary device in this case. The morbid Sondheim-worthy refrain, “kill every one of God’s children to save our own” (which seems to be the moral behind Misty’s realization that Tabbi may be her dearest treasure) is drowned by the many voices in both her and Palahniuk’s head.

Sunday, May 30, 2010

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment