In my anticipation for Gus Van Sant's Milk, I was most curious about the framing style Van Sant employed in his flashback depiction of Harvey Milk’s life and work as both a biopic and as a period film, capturing the salient events and cultural atmosphere of Castro Street and the San Francisco area during the 1970s. Van Sant often tailored his use of camera angles and shots, among other cinematographic tools across his films, in a far more experimental manner than the Hollywood blockbuster to enhance his films' effectiveness conveying the mood and meaning within his settings. His chilling tracking shots that stalked the Columbine-like students in Elephant and the persistent use of distant long-shots, and minimal facial exposure, of the isolated Kurt Cobain character in Last Days represent only a few of his great stylistic devices.

I was pleased by Van Sant’s determination to focus less on the psychological dynamics operating behind Milk’s character in face of great adversity (especially as an allegory for the psychological disintegration common of homosexual characters in Hollywood’s past e.g. Plato in Rebel Without a Cause) for more in-depth focus on the feel and effect of Milk’s role in the gay movement in San Francisco. His greater dedication to the “period film” aspect, and most definitely his juxtaposition of real-life clips of Milk and the gay community, specified the target of the emotional drive of the film. I was brought to tears not so much due to an unearthing of memories of my encounters with anti-gay/bi hostilities but as a result of finally seeing a laudable biopic made the way it should.

It’s great that Van Sant “recruits” us along to remind us how real these events were by (1) positioning our point of view as another protestor within the greater mass in Milk’s rallies and (2) by initially confining his setting inside Castro Street before gradually expanding our exposure (through news broadcasts and such) to the far-reaching effects of and retaliation to the gay movement as he rises to “Mayor of Castro Street.” However, the film’s greatest emotional drive emanated from his humanization of Milk with the voyeuristic shots infringing on the privacy of Milk’s home affairs and Milk’s acrophobic point-of-view shots while he faced a seemingly endless crowd before giving one of his greatest speeches (especially with potential killers in the mass).

Reminiscent of Orson Welles’ style, Van Sant utilized a number of “artsy” metaphoric images to illustrate the disenchantment associated with the pessimistic reality for homosexuals in America. In the scene in which a young homosexual man was murdered in the streets, Van Sant portrayed a close-up reflection of cops surrounding the bloody incident on a side of a whistle dropped on the cement road, possibly belonging to the murdered man. Immediately before, homosexuals recruited to Milk’s cause discussed how it was necessary for them to carry their own whistles so they can protect each other from hate-violence. The police force has not only neglected their victimization but was even suggested to have participated. The irony lies in the traditional icon of the “whistle” representing the “whistle-blowing” role of justice, what the police force should have represented. Just as we are provided a glimpse of Charles Kane’s tragic moment of lost innocence with the object close-up shot of the “Rosebud” in the snow-globe, the whistle serves a similar role for our justice system’s tragic moment of lost innocence.

At the moment Dan White runs through a series of office doorways to assassinate Milk, the Citizen Kane homage is undeniable if we recall Kane running through the many doorways of his gloomy mansion to his second wife’s room and we realize that it was Susan Alexander’s desertion that becomes the final catalyst for his demise and ultimate death. Van Sant perhaps refers to a deeper analogy since these are the walls of a law-making body. We see that the legal system represent a false sense of security that is inefficient in stopping the destructive impulses of hatred on its war-path. This is especially true when the law-enforcement system meters out trivial sentences in proportion to the maliciousness of the crime.

Despite grim images of the diminished efficacy of government, Van Sant provides allegoric reminders of hope with the handicapped mystery caller from Minnesota and the politically-disinterested prostitute, Cleve Jones, he later recruited. The use of Judy Garland’s signature song “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” from Wizard of Oz during a civil rights march may, at first impressions, appear to be a fall-back to a clichéd homosexual motif. However, considering the implications of Milk’s martyred figure in this, even up to today, ongoing gay civil rights movement, it is emotionally on-point and embodies the long journey gay rights activists have to make far from home.

In light of the heavy political and religious polemical discourse, especially with the recent passage of Proposition 8 in California, Van Sant left ample room for, not surprisingly, the gay jokes. Although I was slightly put-off by the “cake-eater” and “gay-recruiter” allusions, I was delighted by the mise-en-scene with Harvey and Scott making out in public beside the “Come In, We’re Open” sign in front of their store and the inclusion of the ultra-feminine ditsy Latin Lover/Housewife stereotype not dissimilar to Robin William’s “mistress/maid” Agador from The Birdcage. Of course, this is not including the dialogued humor!

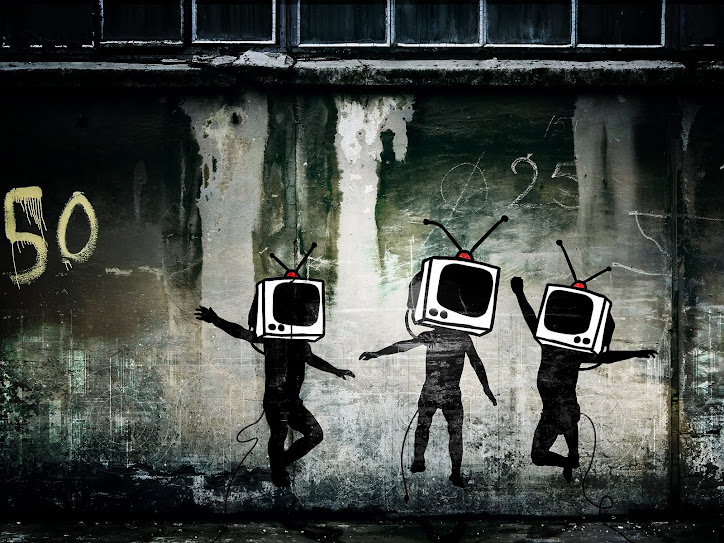

As much as these gay stereotypes may irritate, as any use of categorical assumptions about gay character, they provide a breathy relief to memories of repressive Hollywood years before the 1960s or so when any reference to homosexuality had to be subtly and symbolically incorporated into the script (e.g. Alfred Hitchcock’s Rope about gay serial killers Leopold and Loeb) or any suggestively homosexual characters were depicted as sissy, mentally unstable, or suicidally depressed (e.g. Tom Lee’s character in Vincente Minnelli’s adaptation of the play Tea and Sympathy). As a note, I found the documentary The Celluloid Closet by Rob Epstein particularly useful in understanding the chronological montage of gay film.

Later on, Van Sant even sneaks in some fan service when he self-quotes Elephant: the scene where the camera performs a rotating scan across Milk’s circle of campaign workers in an office alludes directly to the student discussion circle covering the subject of homosexuality in Watt High School. Whereas then you, the viewer, were challenged to pick out which of the students in the circle were gay but had not come out, this time the irony lies in the fact that all of Milk’s campaign recruits were openly gay. There is no necessity for a “witch-hunt” this time.

While the audience is dolefully aware of Harvey Milk’s impending murder, given the historic precedent, Van Sant provides a hopeful “moral” behind Milk’s death as a positive alterative to the disheartening and all-too familiar plot-ending of many gay-innuendo’ed films in the past. The tragic deaths of the homosexual character often appeared to be penitence for their “sin” (not considering films where the homosexual character is converted or assimilated into straight society yet that in itself is “death”). Along with the legacy left behind, epitomized by the crowd of mourners that held lit candles on Castro Street, Milk’s final dying moment with his body faced towards the opera hall represents redemption for his love for Scott, which he was unable to enjoy in this life due to his dedication to the gay rights movement, and his soul (for of course the greater, universal sin).

Sunday, May 30, 2010

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment